Picture this: you’re strolling through Lisbon’s ancient streets, stepping on cobblestones that exist because of a rhinoceros named Ganga. You stop for tea – a word that comes from Portuguese – and later enjoy tempura at a Japanese restaurant, never knowing this dish originated in Portuguese convents. Welcome to Portugal, where every corner holds a story more incredible than fiction.

The Oldest Country You’ve Never Thought About

While empires rose and fell, while borders shifted like sand across Europe, one small nation on the continent’s western edge remained stubbornly, remarkably constant. Portugal isn’t just old – it’s ancient by European standards, holding the distinction of being Europe’s oldest nation-state.

The year was 1139. Crusades raged in the Holy Land, and Europe was a patchwork of feudal territories constantly at war. In this chaos, a determined nobleman named Afonso Henriques declared himself King of Portugal. But here’s where it gets interesting: unlike other medieval kingdoms that expanded, contracted, split, or disappeared entirely, Portugal’s borders, established definitively by the Treaty of Alcanizes in 1297, have remained essentially unchanged for over 700 years.

Think about that for a moment. When Portugal defined its territory, England and Scotland were still separate kingdoms. Germany wouldn’t exist as a unified nation for another 600 years. Italy was centuries away from unification. Yet Portugal stood there, fully formed, a complete nation when the very concept of nation-states was still emerging.

The mystery deepens around Afonso Henriques himself. Modern historians question whether he was truly the son of Count Henry and Teresa of León, suggesting possible illegitimacy or even a complete fabrication of his parentage. But regardless of his bloodline, his achievement remains extraordinary – creating a nation that would outlast empires, survive invasions, and maintain its identity through nearly a millennium of European upheaval.

When Portuguese Monks Invented Japanese Tempura 🍤

The year is 1543. Portuguese merchants, blown off course, land on the Japanese island of Tanegashima. Among the many exchanges that followed – firearms, Christianity, trade goods – one stands out for its delicious unexpectedness: Portuguese missionaries accidentally created one of Japan’s most iconic dishes.

Picture Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in Nagasaki during Lent. Catholic doctrine forbade them from eating meat during this period, so they turned to vegetables and seafood. Their solution? Coat these ingredients in a light batter and fry them quickly – a dish they called “peixinhos da horta” or “little fish from the garden.” The name itself is charmingly Portuguese: even when eating green beans, they couldn’t help but call them fish.

The Japanese were fascinated. They adopted the technique, refined it with their characteristic attention to detail, and named it “tempura” – derived from the Latin “ad tempora quadragesimae,” meaning “in the time of Lent.” The Portuguese missionaries had no idea they were creating culinary history. They were simply trying to observe religious dietary restrictions while making their vegetables more palatable.

Today, walk into any Portuguese tasca and you can still order peixinhos da horta – green beans fried in batter, looking remarkably like their Japanese descendant. It’s a living culinary fossil, a dish that traveled 10,000 kilometers, transformed into something magnificent, while its humble ancestor continued to be served in Portuguese homes, unchanged and unaware of its famous offspring.

A Bookshop That Survived Earthquakes, Wars, and Centuries 📚

In 1732, while Portugal’s gold flowed from Brazil and the Inquisition still held sway, Pedro Faure opened a bookshop in Lisbon’s Chiado district. He couldn’t have imagined that nearly 300 years later, Bertrand would still be selling books from the same location, holding the Guinness World Record as the world’s oldest operating bookshop.

The ironies pile up deliciously. Portugal maintains one of Europe’s higher illiteracy rates, yet it hosts the world’s oldest bookshop. The shop survived the devastating 1755 earthquake that leveled most of Lisbon. It outlasted the Napoleonic invasions, the civil wars, the end of the monarchy, and two dictatorships.

But Bertrand was never just a bookshop. In the 1870s, a group of intellectuals gathered regularly in its back rooms. They called themselves the “Generation of the 70s” – Eça de Queiroz, Antero de Quental, Ramalho Ortigão. These weren’t just writers buying books; they were revolutionaries plotting Portugal’s cultural future, debating politics and literature with a fervor that would reshape Portuguese thought.

The shop’s history took a tragic turn in 1876. José Fontana, the house bookseller who had taken over from the last Bertrand, organized the famous Casino Conferences with Antero de Quental. But tuberculosis ravaged his body while political disappointments crushed his spirit. One evening, in the very spot where the bookshop’s café stands today, Fontana took his own life. The bookshop absorbed this tragedy, as it had absorbed so many others, and continued.

Through the centuries, Bertrand witnessed everything: royal marriages, revolutions, the departure of the court to Brazil, the return of democracy. Each regime change brought new books to burn or ban, new ideas to promote or suppress. Yet the bookshop endured, a constant in a country of variables, its shelves holding not just books but the weight of Portuguese history itself.

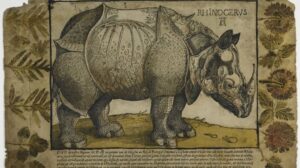

The Rhinoceros That Changed Portuguese Streets Forever 🦏

In 1514, something extraordinary arrived in Lisbon: a white rhinoceros from India, the first living rhino seen in Europe since Roman times. King Manuel I named her Ganga, dressed her in golden armor, and decided to send her as a gift to Pope Leo X. But first, he would parade her through Lisbon to display Portugal’s colonial might.

There was just one problem. January in Lisbon meant rain, and rain meant mud. The king imagined his magnificent rhinoceros, weighed down with decorative armor, trudging through muddy streets, splattering dirt on the royal entourage and gathered crowds. This simply wouldn’t do.

The solution came in royal decrees dated August 20, 1498, and May 8, 1500 – orders to pave Lisbon’s streets with stones. Thus began the tradition of “calçada portuguesa,” the distinctive Portuguese cobblestone patterns that would eventually spread throughout the Portuguese empire.

Workers laid thousands of small stones by hand, creating patterns that turned streets into art. All because a king worried about a rhinoceros making a mess. The irony deepens: Ganga never made it to Rome. The ship carrying her to the Pope sank off the Italian coast. The rhinoceros drowned, her golden armor dragging her down into the Mediterranean.

But her legacy lived on in stone. Today, millions of people walk on Portuguese cobblestones from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro, from Macau to Maputo. They slip on them when it rains, curse them in high heels, photograph their intricate patterns. Few know they exist because five centuries ago, a king wanted to keep a rhinoceros from splashing mud on his parade.

Royal Madness and Everyday Expressions 👑

Language preserves history in ways we rarely realize. Portuguese expressions used daily across the country carry within them tales of royal intrigue, natural disasters, and national trauma that shaped the collective psyche.

Take “Maria vai com as outras” – Maria goes with the others. Every Portuguese person uses it to describe someone who lacks personality, who follows the crowd mindlessly. But its origin is heartbreaking. Queen Maria I, Portugal’s first ruling queen, descended into madness. Declared insane, she was confined to palaces, appearing in public only rarely, always surrounded by ladies-in-waiting who guided her every movement. The people, seeing their queen reduced to this state, would whisper, “There goes Maria with the others.” A queen’s tragedy became a common expression for conformity.

Or consider “Rés-vés Campo de Ourique” – used when something barely avoids disaster. On November 1, 1755, Lisbon experienced one of history’s most devastating earthquakes. The city crumbled, fires raged, a tsunami followed. But the destruction stopped at Campo de Ourique neighborhood, which survived intact. That dividing line between annihilation and survival, that razor’s edge of fate, embedded itself in the language.

Most poignant might be “Ficar a ver navios” – to be left watching ships. After King Sebastian disappeared in battle in Morocco in 1578, Portugal fell under Spanish rule. But people refused to believe their young king was dead. They gathered on Lisbon’s hills, staring at the Tagus River, hoping each arriving ship might carry their lost king home. He never returned.

The expression gained new meaning in 1807 when Napoleon’s troops invaded. They arrived just in time to see the Portuguese royal family’s ships disappearing toward Brazil, literally leaving the French watching the vessels sail away. Two national abandonments, centuries apart, crystallized into three words that every Portuguese child learns.

How a Portuguese Princess Created British Tea Time ☕

In 1662, a Portuguese princess packed her dowry for England. Among the gold, territories, and trading rights, Catherine of Braganza included several wooden crates marked with three letters: T.E.A. – Transporte de Ervas Aromáticas (Transport of Aromatic Herbs). She had no idea she was about to transform British culture forever.

The British knew about tea but considered it medicinal, sold in apothecaries alongside other herbs. Catherine, however, had grown up in the Portuguese court where tea drinking was already an elaborate social ritual, inherited from their Asian colonies. She brought not just the leaves but the entire culture: the delicate porcelain, the specific times for drinking, the foods that accompanied it, the social protocols.

British aristocrats, eager to emulate the new queen, began copying her tea ceremonies. What started as royal mimicry became national obsession. The British added their own touches – the specific time of five o’clock, the finger sandwiches, the hierarchies of who pours – but the foundation was Portuguese.

The ultimate irony? Today, the world thinks of tea time as quintessentially British. Tourists flock to London for afternoon tea at the Ritz. Meanwhile, in Portugal, people drink their coffee, perhaps unaware that their ancestors gave Britain its most famous tradition. Catherine of Braganza created a cultural phenomenon that would outlive empires, but history forgot to credit her.

Those boxes marked T.E.A. contained more than dried leaves. They held a social revolution, a transformation of British identity, all because a homesick Portuguese princess wanted her afternoon cup of tea prepared properly in her new, foreign home.

The Country That Wasn’t: 800 Years of Independence

For eight centuries, maps lied. Between Portugal and Spain, in a mountainous region north of Larouco, existed a country that wasn’t supposed to exist: Couto Misto, Europe’s most successful accidental nation.

Covering just 27 square kilometers, Couto Misto emerged from medieval administrative confusion. Neither Portugal nor Spain could agree on who controlled this remote area, so the locals made a radical decision – they’d control themselves. What followed was 800 years of anarchic freedom that would make modern libertarians weep with envy.

The privileges of Couto Misto citizenship were extraordinary. No military service to either crown. No taxes to anyone. Complete freedom of trade. The right to offer sanctuary to fugitives from both countries. Most remarkably, citizens could choose to be Portuguese or Spanish as convenience dictated, switching nationalities like modern people switch phone plans.

The micronation developed its own peculiar democracy. Three villages – Rubiás, Santiago, and Meaus – rotated leadership, each selecting a judge who served for a year. They had their own legal system, their own economic policies, and absolutely no interest in the wars and conflicts that regularly consumed their larger neighbors.

For 800 years, while Portugal and Spain fought wars, built empires, and lost them again, Couto Misto carried on, forgotten and free. Criminals fleeing justice found sanctuary. Smugglers used it as a base. Young men avoiding military conscription settled there. It was Europe’s hole in the map, a place that existed by not existing.

The end came not through conquest but through bureaucracy. In 1868, diplomats in Lisbon decided to tidy up the map. The Treaty of Lisbon of 1869 split Couto Misto like a cake at a child’s party – Santiago and Rubiás to Spain, Soutelinho da Raia, Cambedo, and Lama de Arcos to Portugal. Eight centuries of independence ended with paperwork. The most successful anarchist experiment in European history disappeared because someone decided the maps looked untidy.

First to End What It Helped Begin

Portugal carries a heavy historical paradox. The nation that pioneered the Atlantic slave trade also became the first to begin dismantling it. This isn’t a story of sudden moral awakening but of slow, complicated progress punctuated by economic interests and occasional flashes of humanity.

In 1570, young King Sebastian, barely 16 and deeply influenced by Jesuit advisors, issued a decree that shocked the colonial establishment: the enslavement of indigenous peoples in Brazil was forbidden. The colonists protested, profits were at stake, but the king held firm. For the first time, a European power had legally recognized that some humans shouldn’t be enslaved.

Twenty-five years later, Portugal banned the trafficking of Chinese slaves. Small steps, limited in scope, but steps nonetheless. The real breakthrough came in 1761 when the Marquis of Pombal, the enlightened despot who rebuilt Lisbon after the earthquake, prohibited importing slaves from the colonies to continental Portugal.

These weren’t acts of pure altruism. Economic changes, political pressures, and strategic considerations all played roles. But Portugal still preceded other nations by decades. While British parliamentarians were still debating the morality of slavery, while American founders were enshrining it in their constitution, Portugal had already begun the legal process of ending it.

The full abolition would take another century, and Portugal’s colonial practices remained brutal long after slavery officially ended. But those first laws, issued when slavery was considered natural and necessary for colonial prosperity, marked the beginning of the end. The first European power to systematically engage in the Atlantic slave trade was also the first to recognize, however imperfectly, that it had to stop.

When James Bond Was Real in Estoril 🕵️

In 1940, while Europe burned, Portugal’s coastal resort of Estoril became the most glamorous refugee camp in history. Neutral Portugal attracted everyone fleeing the war: deposed royalty, Jewish refugees, business moguls, artists, and inevitably, spies. Lots of spies.

Ian Fleming arrived in Estoril in 1941 as a naval intelligence officer. He stayed at the Hotel Palácio, gambled at the Casino Estoril, and watched the most extraordinary collection of humanity ever assembled in one small resort town. At the baccarat tables, German agents sat next to British operatives, everyone maintaining polite fiction while secretly photographing documents and recruiting assets.

The hotels divided along national lines like high school cafeterias. Germans colonized the Atlântico, Grande Hotel do Monte Estoril, and Hotel do Parque. The Allies preferred the Grande Hotel de Itália and Fleming’s own Hotel Palácio. The casino served as neutral ground where everyone mingled, fortunes were won and lost, and information changed hands over champagne.

The cast of characters defied fiction. Juan Pujol García, codenamed “Garbo,” worked as a double agent, feeding false information to the Germans that would prove crucial for D-Day. Zsa Zsa Gabor swept through the casino in furs and diamonds. Leslie Howard, the actor who played Ashley in “Gone with the Wind,” conducted intelligence operations between film shoots.

Fleming absorbed it all: the glamour, the danger, the peculiar civility of espionage conducted in dinner jackets. When he created James Bond a decade later, he drew heavily on his Estoril experiences. The Casino Royale where Bond faces Le Chiffre was inspired by the Casino Estoril where Fleming watched Nazi agents gamble with Jewish refugees’ money.

But the most extraordinary character might have been Portugal itself. While maintaining strict neutrality, the country played every side. Salazar’s regime sold tungsten to the Germans while allowing the Allies to use the Azores. Portuguese officials helped Jewish refugees escape while simultaneously doing business with the Reich. It was cynical, pragmatic, and ultimately successful – Portugal emerged from the war unscathed, its neutrality intact.

Today, the Hotel Palácio still stands, its bar still serving cocktails where spies once exchanged secrets. The casino still operates, though the players now are tourists rather than intelligence operatives. But on foggy nights, when the lights blur and the champagne flows, you can almost imagine Fleming at the baccarat table, watching, learning, creating a legend from the truth of wartime Estoril.

The Portugal You Never Knew Existed

These nine curiosities barely scratch the surface of Portugal’s improbable history. This small country on Europe’s edge has spent centuries quietly influencing the world in ways that history books forgot to mention. From sending rhinoceroses through muddy streets to creating the world’s most famous tea tradition, from harboring wartime spies to accidentally inventing Japanese cuisine, Portugal has left fingerprints on global culture that most people never notice.

The next time you see Portuguese cobblestones, remember Ganga the rhinoceros. When you order tempura, think of those Jesuit missionaries trying to observe Lent. As you sip your afternoon tea, raise your cup to Catherine of Braganza. These stories remind us that history isn’t just about wars and treaties – sometimes it’s about the unexpected ways small actions ripple across centuries and continents.

Portugal’s story is one of unlikely survivals and accidental influences, of royal madness becoming everyday expressions, of a tiny nation that stayed constant while empires rose and fell around it. It’s a reminder that the most interesting history often hides in plain sight, waiting for someone to ask the right questions.

In a world that often feels predictable, Portugal’s curiosities remind us that reality is stranger, funnier, and more interconnected than we ever imagined. Sometimes the smallest countries cast the longest shadows, and sometimes a rhinoceros can change the way we walk through cities forever. 🇵🇹